Introduction

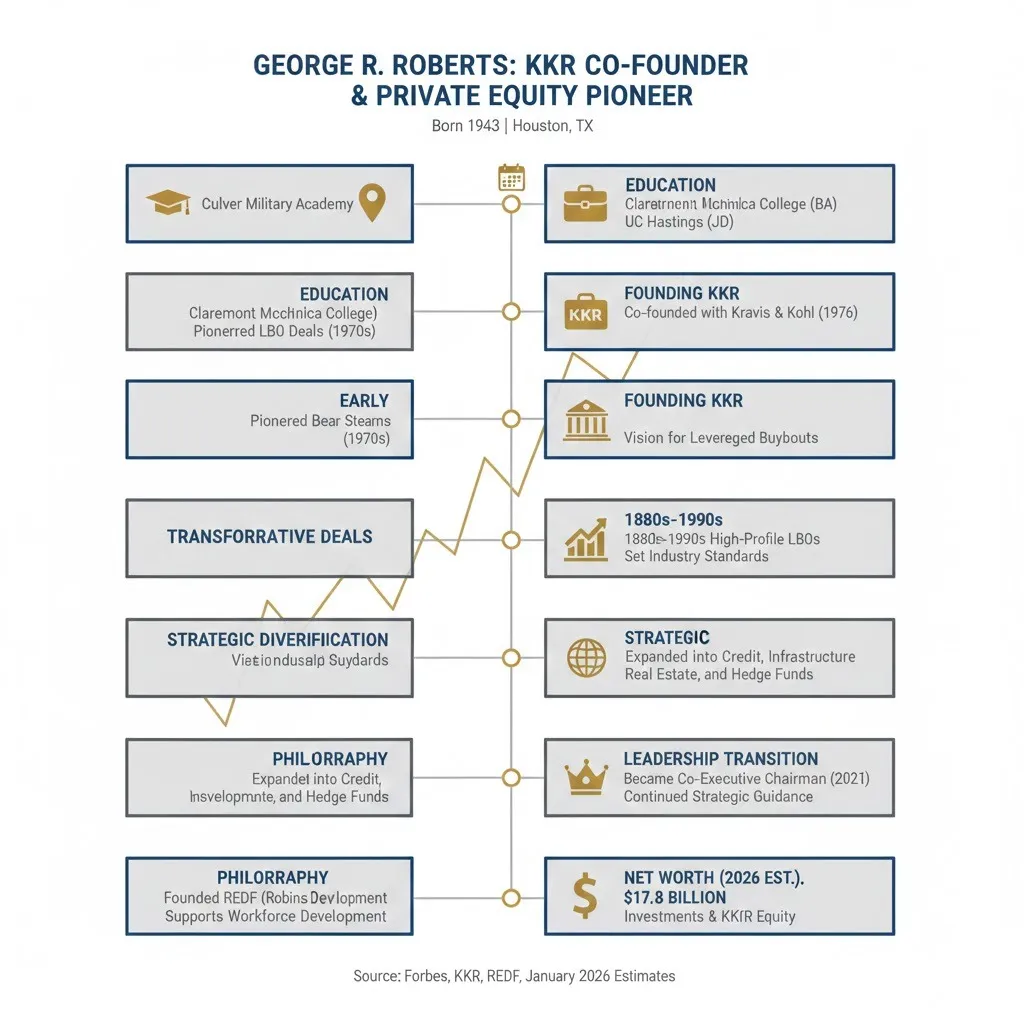

George R. Roberts is a central quantity in the story of modern private justice. As a co-founder of KKR (Kohlberg Kravis Roberts), Roberts helped upskill and scale the leveraged buyout (LBO) model that corrected corporate ownership, governance, and value creation over the last five decades. This article is written in clear, search-friendly language that also uses linguistic variety and NLP-aware style so readers and search engines recognize intent, context, and mastery.

Quick Facts

- Full name: George Rosenberg Roberts

- Born: September 14, 1943

- Age (2026): 82

- Birthplace: Houston, Texas, U.S.

- Education: B.A., Claremont McKenna College (1966); J.D., UC Hastings (1969)

- Known for: Co-founder and Co-Executive Chairman of KKR

- Specialties: Private equity, leveraged buyouts (LBOs), asset management, alternative investments

- Philanthropy: Founder and supporter of the Roberts Enterprise Development Fund (REDF) and cultural institutions

Childhood & Early Life foundations that shaped a financier

George Roberts grew up in Houston, Texas, in a family environment that highlight education, regulation, and civic espousal. He attended Culver Military Academy, where organize academic and cheating training reinforced habits of promptness, shape, and leadership. Those early occurrences in a disciplined school environment often show up in how many personal equity executives talk about corporation and operational rigor later in life.

Roberts then earned a B.A. from Claremont McKenna College in 1966, a tolerant arts education that fostered writing, cogitate, and an understanding of establishment. He followed that with a J.D. from UC Hastings in 1969. While he did not at length practice as a career-long lawyer, the legal training proved directly useful in understanding contracts, deal evidence, and parliamentary nuance is an operational advantage in commercial finance and later in executing compound buyouts.

A formative relationship was with his cousin Henry Kravis. The two shared aspiration and compatible personality that later crystallized into a durable business association. That early social capital, a trusted co-founder with shared experience is a recurring theme in the origin stories of many enduring financial enterprises.

Career Journey step by step

Bear Stearns and the origin of LBO thinking (late 1960s – mid 1970s)

After law school, Roberts joined Bear Stearns’ corporate finance team, a hotbed for dealmaking in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Alongside Jerome Kohlberg and Henry Kravis, he worked on what were then called “bootstrap” transactions essentially small-scale leveraged buyouts that combined borrower financing with operational turnaround plans.

These early deals (examples often cited in histories of the industry include Stern Metals and Incom) served as laboratories for LBO techniques: structuring debt packages, negotiating with owners and bankers, and aligning management incentives with equity upside. The lessons mattered: finance alone doesn’t create sustainable value; structuring incentives and improving operations do.

Plain LBO illustration: imagine you buy a business for $10 million using $7 million of debt and $3 million of equity. Over several years you improve efficiency, grow revenue, and sell for $20 million. After repaying debt, the equity stake multiplies in value. That simple arithmetic powers the LBO rationale, but the true value often comes from managerial and operational changes.

Founding KKR (1976): institutionalizing a model

In 1976, Roberts, Kravis, and Jerome Kohlberg left Bear Stearns and carefully founded Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co. (KKR). The move modified an informal partnership that executed aggressive buyouts into an institutional firm that could raise committed funds from outer investors (pension funds, endowments, wealthy person). This change allowed them to scale, pursue larger transactions, and apply consistent governance and process to a repeatable investing model.

KKR’s early structure emphasized disciplined underwriting, rigorous due diligence, and close post-acquisition involvement. These procedural habits differentiated the firm and made it attractive to limited partners who wanted a reliable allocator of capital.

The boom decades 1980s and 1990s: scale and reputation

KKR rose to wide prominence during the 1980s with increasingly large and headline-grabbing buyouts. The firm’s use of leverage and its willingness to pursue sizeable public-to-private deals caught both attention and controversy. KKR’s deals illustrated how LBOs could convert undervalued or under-managed companies into higher-performing enterprises but they also sparked debates about workforce impacts and financial engineering.

During the 1990s, KKR refined its playbook: more emphasis on range incentives, better operations, and produce exits that realized gains for shareholders. The firm’s development from aggressive debt usage to operational value creation mirrors broader trends in personal equity.

Diversification and resilience 2000s to 2020s

As the private markets evolved, Roberts helped guide KKR’s expansion beyond classic buyouts. New product lines included credit funds (lending strategies), infrastructure, real estate, and alternatives that provide yields less tied to equity-market cycles. This diversification reduced reliance on leveraged buyouts alone and created recurring-fee income streams (management fees, credit interest) that smoothed performance across cycles.

This strategic expansion changed KKR into a multi-asset manager capable of serving a broader set of institutional clients and of capturing more parts of the capital structure from lending to equity.

Leadership transition and current role

Roberts and Kravis served many years as co-CEOs and senior leaders. In 2021 they stepped back from day-to-day executive duties and transitioned to Co-Executive Chairmen roles. In this capacity they remain influential setting culture, mentoring successors, helping with major strategic decisions, and participating in key investment committees while delegating operational leadership to a newer generation of executives.

This leadership handoff is important: it demonstrates succession planning, an emphasis on governance, and the stabilization of KKR’s identity beyond its founders.

Major Achievements distilled

Key accomplishments

- Co-founded KKR (1976), which became a global private equity leader.

- Helped refine and scale the LBO model into a repeatable institutional strategy.

- Guided KKR’s diversification into credit, infrastructure, real assets, and real estate.

- Founded philanthropic vehicles (notably REDF) focusing on social enterprise and workforce attachment.

- Played an enduring role in corporate governance debates and private-market institutionalization.

Achievement table

| Achievement | Period | Why it matters |

| Co-Founded KKR | 1976 | Created a durable, institutional private equity franchise |

| Early LBO deals | 1960s–70s | Pioneered techniques for buyouts and operational turnarounds |

| Diversified product lines | 2000s–2010s | Reduced cyclicality and increased recurring-fee revenue |

| Leadership transition | 2021 | Ensured continuity and governance for the firm |

| Founded REDF | 1990s+ | Applied investment thinking to social enterprise and jobs creation |

Net Worth & Financial Status transparent, contextual

Estimating the personal wealth of a founder of a private markets firm is necessarily approximate. Much of the value resides in illiquid carried interest, private equity stakes, and concentrated shareholdings in the firm or portfolio companies.

- Common public estimate (2026): ~US$17.1 billion (widely quoted by financial trackers).

- Sources of income and value: Equity stake in KKR, carried absorption on successful funds, pension/fees, private investments, and board or trustee reimbursement.

- Why the numbers vary: Private stakes are hard to value accurately; carried interest is realized over long perspective and depends on exits and valuations; public-market equivalents (KKR shares) oscillate.

How Roberts earns money

- Equity ownership: Direct holdings in KKR and in in private held portfolio corporation.

- Carried interest: Long-term incentive repayment tied to fund production.

- Management fees / dividends: Reoccur cash flows derived from KKR’s fee income and issuance.

- Personal investments & trusteeships: Non-KKR assets that may include real property, private holdings, and generous funding.

Investment Approach & Strategy practical, replicable ideas

Roberts’ approach blends financial engineering with operational improvement and people-centered value creation. Below are the recurrent themes and practical lessons that make the KKR model effective:

- Operational discipline over pure leverage: Use debt prudently, but prioritize fixing processes, systems, and management practices to create durable value.

- Long-horizon orientation: Private equity works best with a patient timeline to implement strategy, restructure, and re-position businesses.

- Portfolio and product diversification: Build capabilities across credit, infrastructure, and real assets to balance risk and access multiple return drivers.

- Human capital and leadership development: Invest in management teams, train them, and align incentives. People are the multiplier of operational changes.

- Social awareness: Deploy capital with an eye toward community impact (e.g., REDF-style social enterprises), recognizing reputational and societal dimensions.

Actionable micro-playbook:

Assess the business: Identify one operational metric to improve (e.g., working capital days) and quantify how a 5–10% improvement affects cash flow.

Align incentives: Design compensation that rewards sustained improvement, not short-term cost cuts.

Plan exits early: Build the exit story at acquisition what will make the company more valuable to the next owner?

Diversify thinking: Don’t view leverage as the only tool; consider product, market, and business-model changes.

Simple example of his approach applied: When KKR acquires an industrial manufacturer, they often pair financial restructuring with investments in automation, lean manufacturing practices, and salesforce incentives. The combined effect is higher margin, better cash conversion, and an attractive exit multiple.

Philanthropy, Boards & Public Influence beyond finance

Roberts has used his resources and influence to support education, social enterprise, and cultural institutions.

- REDF (Roberts Enterprise Development Fund): A nonprofit created to incubate and support social enterprises that hire disadvantaged individuals. REDF treats these organizations as mission-driven businesses that can be strengthened through capital, technical assistance, and entrepreneurship support.

- Education and trusteeships: Roberts has been active with Claremont McKenna College and other academic institutions, supporting scholarship and institutional development.

- Arts and culture: Philanthropic support includes organizations such as the San Francisco Symphony and ballet companies; these gifts reinforce civic cultural infrastructure.

Roberts’ philanthropic pattern shows an inclination to apply investment discipline to social problems using measurement, accountability, and capacity-building rather than unrestricted grantmaking alone.

Controversies & Criticisms balanced context

As an architect of large leveraged buyouts, Roberts and KKR inevitably occupy a contested space in public debate. Here are the principal critiques and counterpoints:

- Heavy leverage and employment concerns: Critics argue that LBOs can impose heavy debt burdens and incentivize cost-cutting that hurts employees. Proponents counter that restructuring can rescue otherwise failing businesses and preserve jobs by restoring profitability.

- Public image of private equity: Popular narratives (such as Barbarians at the Gate) painted buyout firms as aggressive corporate raiders. Modern private equity emphasizes stewardship, governance, and operational upgrades — though skepticism persists.

- Concentration of wealth: The scale of private-market profits raises broader questions about tax policy, distribution, and the social role of billionaire philanthropists. Roberts has responded with philanthropy and social investments, but debate remains about systemic reform.

Important: many criticisms apply to the private equity industry at large; individual managers and firms differ widely in approach and outcomes.

Timeline quick reference

- 1943: Born in Houston, Texas.

- 1962: Graduated Culver Military Academy.

- 1966: B.A., Claremont McKenna College.

- 1969: J.D., UC Hastings College of the Law.

- 1969–1976: Bear Stearns corporate finance and early LBO work.

- 1976: Founded KKR with Kravis and Kohlberg.

- 1980s–1990s: High-profile leveraged buyouts and operational evolution.

- 2004–2011: Expansion of product lines: credit, infrastructure, real estate.

- 2021: Transitioned to Co-Executive Chairman, stepping back from daily CEO duties.

- 2026: Active in governance, philanthropy, and public speaking on infrastructure and long-term investing.

Personal Life short profile

- Married: Leanne Bovet (married 1968 died 2003); later married Linnea Conrad (2010).

- Children: Three.

- Private persona: Generally private; focuses on family, mentoring, philanthropic engagements, and thought leadership within the investment community.

FAQs

A: Public estimates put his net worth near US$17.1 billion. These numbers use public and private data, so they can change.

A: Yes. In 2021 he moved from Co-CEO to Co-Executive Chairman. He still guides strategy and sits on committees.

A: He graduated from Culver Military Academy, Claremont McKenna College (BA), and UC Hastings (J.D.).

A: REDF (Roberts Enterprise Development Fund) is a nonprofit that invests in social enterprises to create jobs for people facing big challenges.

A: KKR helped shape private equity and the leveraged buyout model. It later grew into a multi-asset manager with global reach.

Examples & Mini Case Study practical demonstration

Mini case: KKR buys a mid-sized manufacturing company for $500 million.

- Capital structure at acquisition: $350M debt, $150M equity.

- Year 1 focus: Operational diagnostics reduce downtime, improve supply chain, implement lean processes, and upgrade sales incentives.

- Year 3 outcomes: New product introductions and efficiency gains increase revenue 20% and margins expand.

- Exit: Company sold for $800M. After repaying debt, equity holders realize a multiple on their invested capital.

This concrete example shows how financial engineering plus operational improvements can produce value for investors and stakeholders when executed responsibly.

Table: Common Terms

| Term | Meaning |

| Private equity | Firms that buy companies to improve and sell them later. |

| LBO (Leveraged Buyout) | Buying a company using large loans. |

| Carried interest | A share of profits for fund managers. |

| AUM (Assets under management) | Total money a firm manages for clients. |

| REDF | Roberts’ nonprofit that helps people get jobs. |

Conclusion

George R. Roberts’s journey from a young financier in Houston to one of Wall Street’s most influential private equity pioneers is a story of vision, resilience, and reinvention. As the co-founder of KKR, he not only redefined corporate finance through leveraged buyouts but also helped build an institution that has shaped the modern global economy.

Beyond business, Roberts’s deep commitment to philanthropy through the Roberts Enterprise Development Fund (REDF) and other initiatives highlights his belief in using wealth for social progress. Even in his later years, his strategic foresight and leadership continue to inspire a new generation of investors, entrepreneurs, and changemakers.

In 2026, George R. Roberts remains more than a billionaire financier he’s a symbol of transformative capitalism, balancing profit with purpose, and leaving an indelible mark on finance, philanthropy, and leadership itself.