Introduction

Ernest García II is a polarizing figure in the American automotive and finance sectors. To some he is a visionary who turned distressed assets into a vertically integrated empire; to others he is a controversial operator whose past legal problems and opaque transactions prompt skepticism. What unites both perspectives is acknowledgement of scale: García’s influence on the used-car retail and subprime auto finance markets is undeniable.

Early Life & Background

Ernest García II was born May 1, 1957, in Gallup, New Mexico. He grew up in a family that ran small businesses; his father co-owned a liquor store and at one point served as Gallup’s mayor. That early exposure to entrepreneurship and local commerce shaped García’s practical understanding of business: customer flows, cash cycles, and the leverage of local relationships.

Small-town origins often produce two traits that are visible in García’s career: an appetite for risk and a preference for pragmatic problem-solving over abstract theory. Whether placing capital bets on real estate parcels or buying and refurbishing used vehicles for resale, García’s instincts leaned toward tangible assets things you can inspect, move, monetize.

Education & Early Ventures

García attended the University of Arizona, though sources differ on whether he completed a degree at that time. What is clearer is that formal credentials were not the primary currency of his early progress. He moved into real estate development, land deals, and finance in the 1980s, building relationships with lenders, brokers, and auction houses networks that would later underpin his auto retail and lending operations.

Early ventures focused on leveraging capital and identifying undervalued assets. In the late 1980s he was active in Arizona real estate cycles, which gave him both opportunity and exposure to shifting credit markets. These years built a pattern: identify distressed/underserved markets; design a financing or operational structure to extract value; scale through repeated application.

1990 Felony Conviction & Bankruptcy

A defining and indelible episode in García’s life occurred in 1990. He pleaded guilty to felony bank fraud in connection with transactions involving Lincoln Savings & Loan. The underlying scheme, as reported in public records, involved arrangements where García acted as a “straw borrower” to obtain a US$30 million line of credit, while concealing Lincoln’s stake in risky Arizona land transactions from regulators.

The legal outcome included probation García was placed on three years of probation and a collapse of his personal and corporate finances that culminated in bankruptcy. For many entrepreneurs, a conviction and bankruptcy of this magnitude would end public careers. For García it became a pivot.

It is important to treat this chapter with factual precision: the conviction is part of the public record and influences how investors, regulators, and journalists interpret subsequent moves. At the same time, García’s later track record demonstrates a capacity to rebuild capital and corporate control at large scale.

Acquisition of Ugly Duckling & the Turnaround

In 1991 García purchased Ugly Duckling, a bankrupt rent-a-car franchise, for less than $1 million. At the time, Ugly Duckling was an asset with physical locations and brand recognition but without momentum. García recognized an adjacent opportunity: merge that network with a nascent auto finance operation targeted at subprime customers who had limited access to prime credit.

This move demonstrated two strategic instincts:

- Asset arbitrage monetize existing physical infrastructure at a discount; and

- Niche focus targets a customer segment mainstream dealers avoided.

García layered finance products (installment contracts), ancillary revenue lines (warranties, insurance), and operational improvements (vehicle inspection and refurbishment). The company grew, and in 1996 Ugly Duckling was taken public under the ticker UGLY, raising roughly US$170 million. Public capital accelerated expansion dealership rollouts, inventory purchases, and lending capacity.

By 2002 the company was taken private and rebranded as DriveTime. The privatization allowed García and partners to manage long-term strategy outside quarterly investor pressures and public scrutiny, enabling vertical integration moves and the creation of subsidiary operations focused on financing and risk management.

Building Drive Time: Strategy & Growth

DriveTime evolved into a vertically integrated platform where retail, financing, and post-sale services are tightly coupled. That integration allowed García to capture multiple layers of margin and exert operational control over the customer lifecycle.

Business Model & Strategy

DriveTime’s model centers on several durable elements:

- Vertical integration. DriveTime does more than sell used cars: it underwrites loans, services vehicles, offers warranties, and provides ancillary insurance products. By owning both the origination and servicing functions, the company reduces dependency on third parties and preserves revenue streams that would otherwise be captured by financiers, insurers, or repair shops.

- Subprime specialization. DriveTime deliberately focuses on buyers with imperfect credit. Traditional franchised dealers and prime lenders often choose to avoid those customers. DriveTime developed internal risk models and underwriting heuristics to price and manage subprime exposures, accepting higher interest margins commensurate with default probabilities.

- Scale in vehicle flows. The enterprise buys cars in high volumes (auctions, trade-ins, fleet purchases), inspects and refurbishes them, and resells through a network of lots and online channels. High-volume purchasing provides bargaining leverage, and centralized inspection programs enforce quality standards.

- Operational controls. Inspection centers, refurbishment protocols, and 14-day quality windows (as publicly described in various profiles) reduce returns and reputational problems while allowing a broad purchase set at auction.

These elements combine to create a defensible business in a thin-margin sector: by owning the financing and service stack, Drive Time controls more of the economics and the customer relationship.

Expansion & Subsidiaries

Over time DriveTime spawned or integrated specialized entities to distribute risk and streamline operations:

- Bridgecrest Acceptance Corporation a servicer/holdco for installment contracts and receivables.

- GO Financial an attempt to scale retail financing products.

- SilverRock Group a provider of insurance, extended warranties, and service contracts.

Each arm addresses a different slice of the customer lifecycle and monetizes parts of the business that would otherwise leak to partners. This architecture mirrors modern fintech strategies: originate at point-of-sale, retain or service receivables, and sell ancillary guarantees.

Founding & Role in Carvana

In 2012, entrepreneurially minded executives within the DriveTime orbit notably Ernest García III, son of García II launched Carvana as a digitally native used-car marketplace. Carvana’s premise was straightforward but ambitious: make buying a used car as simple as buying any other consumer good online.

Caravan introduced several innovations:

- An end-to-end digital buying experience, including financing and trade-in valuation.

- Home delivery or self-service pickup from so-called “car vending machines.”

- Transparent vehicle histories and online inspections.

Caravan’s 2017 IPO made it a publicly traded company, separate from Drive Time but tied through investment stakes and overlapping ownership. García II retained significant shareholding and influence either directly or through layered trusts and holding structures. While not always involved in day-to-day operations, his financial backing and governance connections created meaningful alignment between Drive Time’s operational logic and Caravan’s digital retail ambitions.

Carvana represented a self-disruptive step by the family and affiliates: rather than merely defend traditional channels, they invested in a model that could redefine customer acquisition and inventory flow.

Recent Business Moves & Stock Sales

As public markets and private cash needs evolved, García II (and related family entities) executed sizable insider stock sales, frequently through Rule 10b5-1 trading plans. These prearranged schedules allow insiders to sell shares according to an automated plan, insulating them against accusations of opportunistic timing.

Public reporting indicates some large sales occurred in 2021, with multibillion-dollar totals attributed to the family’s monetization actions. These sales have multiple interpretations:

- Liquidity management. Transforming paper wealth into diversified assets or funding other ventures

- Risk hedging. Realizing gains while conditions are favorable.

- Market signaling. For some investors, large insider sales can be perceived as reduced confidence; for others, they are routine financial planning.

The structure of control is also complex: direct holdings, trusts, and multiple legal vehicles can preserve governance control even as a portion of economic interest is sold. This separation matters for both corporate control analysis and net worth calculations.

Major Achievements & Distinctions

García II’s career contains several noteworthy accomplishments:

- Turnaround execution. Buying Ugly Duckling from bankruptcy and scaling it into a national used-car and finance company is a textbook turnaround: acquire distressed assets cheaply, inject operational discipline, and extract value across multiple revenue lines.

- Building a vertical stack. By combining retail and financing, García avoided commoditization of sales and preserved margin capture.

- Backing digital disruption. Supporting Carvana signaled both strategic foresight and willingness to invest in business model innovation.

- Resilience. Returning from legal and financial collapse to build multibillion-dollar holdings demonstrates capital formation capability and operational persistence.

Each distinction is paired with caveats: success in business does not erase legal history or reputational concerns but these achievements explain why García II remains central to narratives about the used-car and subprime finance ecosystem.

Net Worth & Financial Profile (2025)

Estimating the net worth of individuals with complex ownership structures is inherently imprecise. García II’s wealth blends public equity (Carvana), private operating companies (DriveTime and affiliates), and real estate holdings. Public trackers provide ranges that reflect market valuations and available filings.

Net Worth Estimates (2025)

| Source | Estimated Net Worth | Notes / Caveats |

| Wikipedia (Jan 2025) | US$20.7 billion | Aggregates public filings and wealth trackers |

| Grizzly Bulls (Oct 2025) | US$22.1 billion | Real-time Net Worth as of Oct 2025 |

| Traders Union & other estimates | Varies | Dependent on share prices and private asset valuations |

A practical working range for public-facing summaries is US$20–22 billion in 2025, acknowledging that swings in Carvana’s market capitalization or fresh valuations of DriveTime’s private assets could push the estimate materially higher or lower.

Sources of Wealth

- DriveTime operations: retail sales margins, interest income from in-house finance contracts, and fees from warranties/insurance.

- Carvana stake: public equity whose value fluctuates daily.

- Real estate & direct investments: holdings in Arizona and other jurisdictions, including high-value properties.

- Other private investments: minority stakes, structured assets, and cash equivalents.

Concentration & Market Risks

The concentration of wealth in auto retail and auto-finance and, specifically, in a public equity whose price is volatile exposes García to several macro and idiosyncratic risks: economic cycles affecting auto demand, interest rate shifts that change borrower default dynamics, and regulatory scrutiny on subprime lending practices.

Controversies, Risks & Criticism

A balanced profile must catalogue controversies and structural vulnerabilities.

The 1990 Conviction

García’s felony bank fraud conviction remains a salient fact in background checks and media profiles. Critics cite it as a character warning; defenders note legal rehabilitation and subsequent compliance. The conviction colors investor sentiment and public trust.

Lawsuits & Conflicts

Historical litigation for example, allegations around discounted acquisition of company-owned properties in the late 1990s feed narratives of conflicts of interest. Even if legal outcomes did not fully dismantle García’s enterprises, these episodes spotlight governance and transparency questions.

Insider Sales & Signaling

Large insider sales prompt debate: are they standard wealth management or a signal of decreasing confidence? While 10b5-1 plans mitigate timing concerns, perceptions persist in trading communities.

Business Model Vulnerabilities

Operating at the subprime margin entails intrinsic hazard:

- Default risk. Subprime borrowers are more sensitive to unemployment and interest rate changes.

- Regulatory risk. Consumer protection rules, state-level finance licensing, or federal oversight can alter economics.

- Inventory churn risk. Used-car prices are volatile; sudden price drops can erode margins.

Inter-company Transactions & Transparency

Allegations or perceptions that DriveTime and Carvana transact at non-arm’s-length terms raise governance questions. When affiliated entities trade inventory between them, external investors and regulators sometimes probe whether financials mask underlying earnings management or risk shifting.

Personal Life & Legacy

Family & Residences

García II is married and has children, including Ernest García III, who is widely identified with Carvana’s founding and leadership. Reports also highlight high-profile real estate ownership including properties in Arizona and a reported apartment in a New York landmark building.

Public Persona & Reputation

García tends to maintain a low personal profile. That low visibility, combined with a past conviction, creates a distinctive public image: a powerful, private operator who prefers transactions to headlines. To colleagues and industry insiders, he is often described as shrewd and strategic; to critics, as secretive and aggressive.

Legacy Outlook

In time, García II’s legacy will likely be evaluated on two axes:

- Operational impact: did DriveTime and affiliated ventures change how used cars are financed and retailed?

- Governance and ethics: did his career demonstrate sustainable, transparent stewardship, or would legal and governance issues overshadow operational achievements?

Both narratives will shape retrospective assessments.

Lessons & Motivational Insights

From García’s arc we can derive practical lessons both tactical and philosophical — that apply to entrepreneurs and business students.

- Failure can be a catalyst. Legal and financial collapse did not end García’s enterprise-building; it forced reorientation and strategic improvisation.

- Find the overlooked market. Underserved segments (subprime borrowers) present outsized opportunities when approached with disciplined underwriting.

- Control the entire customer journey. Vertical integration (sale → finance → warranty → service) reduces dependency and creates sticky revenue.

- Use structures to manage optics. Preplanned trading plans and trust vehicles can achieve liquidity goals while managing market perception.

- Disrupt yourself. Investing in digital-first models (Carvana) demonstrates the value of threat anticipation over complacency.

- Transparency matters. Past legal issues amplify the importance of governance and open reporting. Successful operators must build trust actively.

These lessons are practical but not prescriptive: outcomes depend on execution, market context, and regulatory environment.

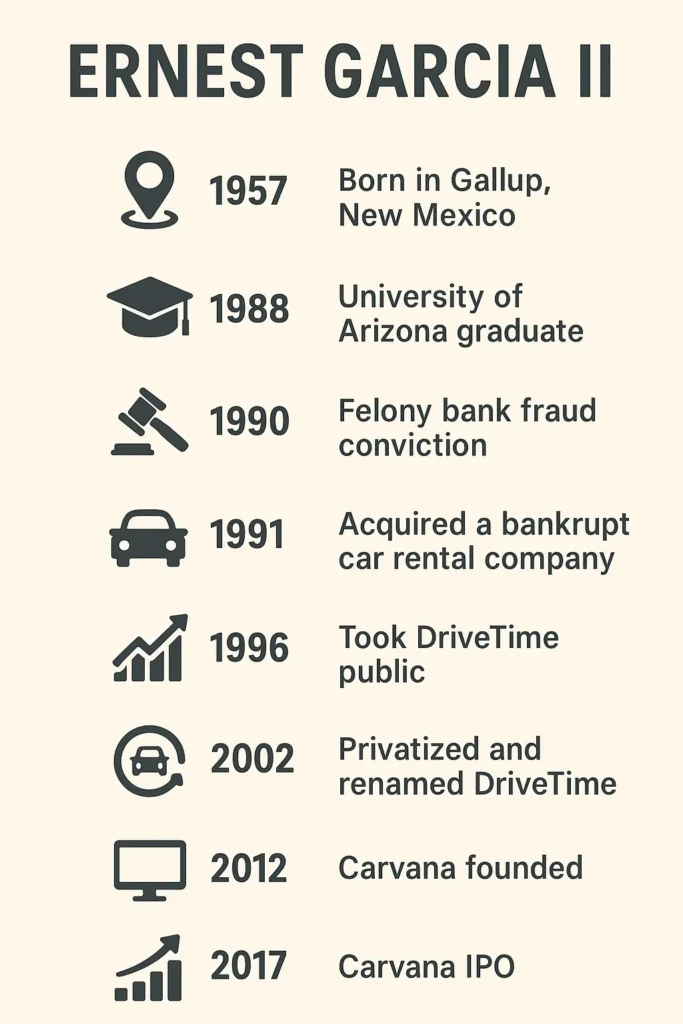

This infographic tracks the pivotal moments that shaped his journey from early challenges to creating two of America’s biggest used-car empires DriveTime and Carvana.

FAQs

A: He pled guilty to felony bank fraud linked to arranging a US$30 million line of credit via straw-borrower schemes, helping Lincoln Savings & Loan hide ownership of risky Arizona land from regulators.

A: By acquiring a failing rental franchise, merging with finance operations, improving quality, expanding dealerships, adding financing & warranty arms, going public in 1996, then later taking it private and rebranding as DriveTime in 2002.

A: His son, Ernest García III, co-founded Carvana in 2012. In 2017, Carvana went public, and García II kept a major shareholding and influence. He doesn’t always hold executive titles there but exerts control via ownership.

A: Estimates vary, but public sources like Wikipedia put him at ~US$20.7 billion as of early 2025. Grizzly Bulls estimates ~US$22.1 billion in October 2025.

A: Major risks include stock market volatility (Carvana shares), rising default rates on subprime loans, regulatory changes affecting auto finance, and public trust given his criminal past and insider transaction scrutiny.

Conclusion

Ernest García II’s story is a study in contrasts: a public record marked by a serious legal conviction and bankruptcy, followed by relentless reconstruction that produced a vertically integrated auto retail and finance empire. He transformed distressed, tangible assets into scalable businesses by combining pragmatic operational discipline with aggressive financial structuring. From buying a bankrupt rental chain for a bargain price to building Drive Time’s financing stack and backing the disruptive Caravan experiment, García repeatedly found opportunity where others saw only risk.

That duality remarkable operational Success coupled with persistent governance and reputational questions will define how history remembers him. On one hand, García’s ability to identify underserved markets, monetize ancillary services, and capture margin through vertical integration demonstrates rare entrepreneurial acumen. On the other hand, the 1990 conviction, subsequent lawsuits, and periodic insider sales mean his legacy will always be evaluated through the lenses of ethics, transparency, and regulatory oversight.

For readers and analysts, the practical takeaway is balanced: study García’s methods for spotting and exploiting market inefficiencies, but also treat his career as a reminder that growth without clear governance and transparent stewardship invites scrutiny. For entrepreneurs, his journey reinforces that resilience, creative financing, and operational control can rebuild fortunes but sustained success at scale also requires building trust and institutional safeguards.