Introduction

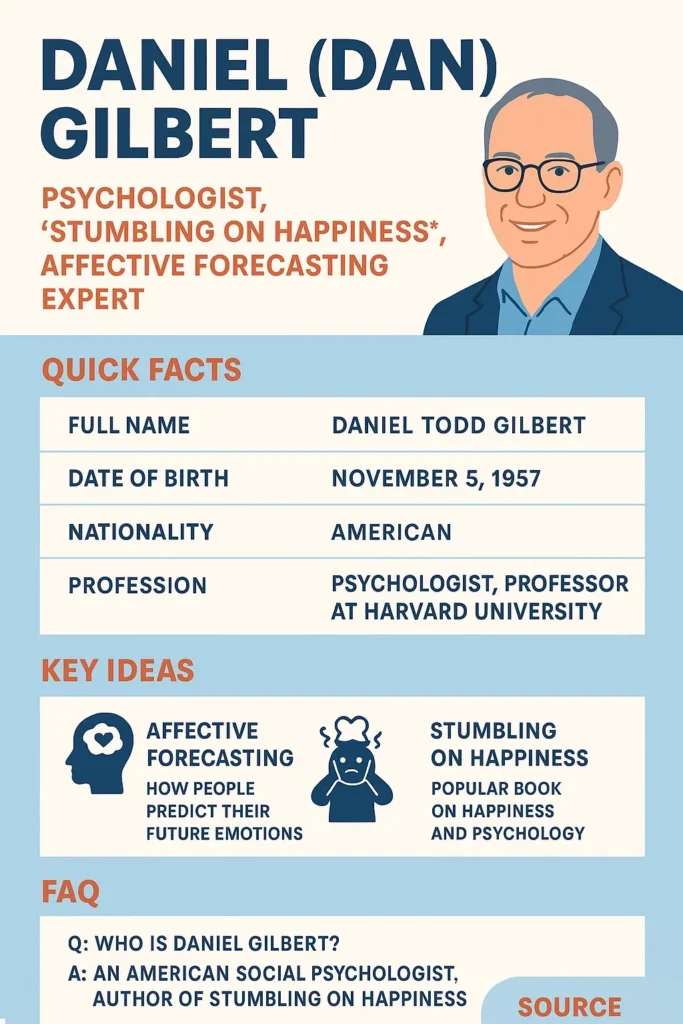

Daniel (Dan) Gilbert is widely take as a leading figure in social demeanor and the science of emotion forecast. Best known for introducing research on emotive augur, the cognitive process by which people predict their future feelings, Gilbert has determine how analysis, economists, legislators, and everyday people think about happiness, decision-making, and emotional conversion. He is also the smash author of Slip on Happiness, a book that interpret decades of probing findings into an reachable chronicle.

Quick Facts Table

| Item | Detail |

| Full Name | Daniel Todd Gilbert |

| Date of Birth | November 5, 1957 (public records & profiles) |

| Nationality | American |

| Profession | Social Psychologist, Professor (Harvard University) |

| Major Book | Stumbling on Happiness (2006) |

| Known For | Affective forecasting, impact bias, social cognition, decision-making, synthetic happiness |

| Spouse | Marilynn Oliphant (publicly listed) |

| Education | BA in Psychology (University of Colorado Denver), PhD in Social Psychology (Princeton University, 1985) |

| Awards & Honors | Multiple recognitions (Royal Society Prize for Science Books for Stumbling on Happiness, APA honors, fellowships, membership in major academies) |

Childhood & Education

Early Life

Daniel Todd Gilbert was born in Ithaca, New York, on November 5, 1957. From early on, he demonstrated curiosity about human thought and feeling, a theme that would define his academic career. Public records and profiles emphasize his intellectual curiosity more than intimate family details; Gilbert’s professional life and scholarship are the predominant publicly documented elements of his biography.

Education

- High School & Early Choices

Gilbert’s educational path shows examples of non-linear academic trajectories that later inform his work about expectation versus reality. Some sources have mentioned early challenges and unconventional steps before formal higher education; however, most verified public records focus on his BA and PhD credentials. - Undergraduate Degree

He earned a BA in Psychology from the University of Colorado Denver. This undergraduate foundation introduced him to the empirical methods and theoretical frameworks that shaped his later research. - Doctorate (PhD)

Gilbert received his PhD in Social Psychology from Princeton University in 1985. His doctoral training and early publications developed into a research program centered on judgment, decision-making, and how humans understand both themselves and others.

Academic Career & Research Journey

Early Career

After completing his PhD, Gilbert accepted a faculty appointment at the University of Texas at Austin (mid-1980s). There, he taught courses in social psychology, designed laboratory and field experiments, and began a steady stream of publications examining biases in reasoning, social inference, and the psychology of prediction.

Harvard & Key Focus Areas

In 1996, Gilbert joined the faculty at Harvard University, where he became the Edgar Pierce Professor of Psychology. At Harvard, he led a research group and contributed to both theoretical and applied strands of psychological science. His principal areas of interest include:

- Affective forecasting is how people predict emotional reactions to future events.

- Social inference is how we interpret other people’s minds and motives.

- Decision-making under uncertainty;

- Emotional adaptation is the process by which individuals recover or acclimate to new circumstances, and

- Synthetic vs. natural happiness how context and cognitive processes shape perceived wellbeing.

Gilbert’s lab produced influential empirical papers that identified systematic mistakes people make when anticipating future feelings, and these findings have been integrated into behavioral economics, clinical practice, public policy design, and everyday self-help strategies.

Key Concepts & Major Research

Below are the major theoretical contributions and the empirical phenomena that Gilbert and collaborators documented. Each entry is phrased to optimize both human comprehension and semantic coverage for search and NLP systems.

Affective Forecasting

Affective forecasting is the umbrella term Gilbert helped popularize. It refers to the cognitive work of predicting one’s own future emotions, predicting both valence (positive vs negative) and intensity/duration.

Key empirical patterns:

- People often overestimate the intensity of their future emotions.

- People often overestimate the duration of emotional reactions.

- People underestimate the speed of adaptation, how quickly life circumstances cease to dominate emotional experience.

These tendencies produce predictable decision-making errors when individuals choose based on inaccurate emotional forecasts (e.g., selecting a career or city because one imagines long-lasting bliss that often proves transient).

Everyday Examples

- Expecting permanent elation after a promotion, only to return to baseline levels of happiness after routine work stress resumes.

- Believing that a breakup will cause long-term despair, but discovering resilience and emotional recovery sooner than predicted.

Impact Bias, Fiscalism & Immune Neglect

To explain the mechanisms underlying forecasting errors, Gilbert’s work identified several interlocking biases:

| Term | Definition | Practical Effect |

| Impact Bias | The tendency to overestimate the intensity and duration of emotional responses to future events. | Leads to overvaluing short-term outcomes when making decisions. |

| Focalism | Fixating on a specific event and failing to consider other life circumstances and competing influences. | Causes overattention to a single factor and underestimation of contextual influences. |

| Immune Neglect | Underappreciating the mind’s coping mechanisms (psychological immune system) that help people recover from negative events. | Results in overpredicted sadness and underpredicted recovery potential. |

These constructs combine to explain why people “miswant” desire things they expect will bring more happiness than they ultimately do.

Misacting & Synthetic Happiness

Gilbert and colleagues use the term miswanting to describe the mismatch between what people think will make them happy and what actually does. Connected to this is the distinction between natural happiness (stemming from desired outcomes) and synthetic happiness (constructed happiness that emerges from reframing, acceptance, or adaptation). The latter shows that people can arrive at stable contentment through cognitive processes, even when external circumstances don’t match their prior preferences.

Experimental Foundations & Measurement

Gilbert’s empirical program used randomized experimental designs, longitudinal follow-ups, and survey measures to show forecasting errors across domains (romantic decisions, financial windfalls, medical outcomes, job changes). Researchers compared predicted affect reported before events to actual affect reported after events, revealing systematic discrepancies.

Everyday Applications: How Gilbert’s Research Helps Us

Gilbert’s findings are highly actionable. Below are concrete ways people and institutions use affective forecasting research.

Better Decision-Making

- Before major life changes (jobs, relocations, relationships), actively seek retrospective accounts from people with lived experience.

- Separate short-term affective spikes from long-term well-being gains. Avoid basing permanent commitments solely on ephemeral emotions.

Goal-Setting & Expectations

- Use realistic timelines: assume adaptation when estimating how long benefits or harms will last.

- Set incremental targets and check-ins instead of relying on a single prophetic forecast.

Coping with Negative Events

- Remember the mind’s capacity to reframe and recover: rely on proven coping strategies (social support, cognitive reframing, behavioral activation).

- Use awareness of immune neglect to temper anticipatory anxiety about future hardship.

Policy, Business & Marketing

- Conduct economists incorporate affective prophesy into models of saving, indemnity uptake, and welfare design.

- Marketers should be mindful: purchaser mispredict the hedonic payoff from purchases; ethical retail can mitigate buyer regret.

- Public health conciliation can design communications that reflect conversion processes to avoid checking fear appeals.

Criticism & Limitations

Gilbert’s work is influential, but like all scientific programs, it faces scrutiny and boundaries.

Empirical & Methodological Critiques

- Laboratory vs. Real-World

Some critics argue that certain experimental paradigms simplify complex, long-term experiences. Real-world forecasting may involve richer contexts that alter forecasting accuracy. - Question Framing & Measurement Artifacts

How researchers ask forecasting questions vs. how they measure later effects may introduce artifacts. Differences in scale, timing, or reference frames can produce apparent forecasting errors that partly reflect measurement mismatch. - Cultural & Individual Variation

Adaptation and affective forecasting may vary by culture, socioeconomic status, personality traits, and life stage. The general patterns identified by Gilbert might not be uniform across all populations. - Scope: Not All Emotions Adapt Equally

Some deeply identity-linked or traumatic outcomes resist full adaptation; research acknowledges that severe negative events often have longer-lasting emotional consequences.

When Theories May Not Apply

- Chronic illnesses, bereavement, and identity-threatening experiences may involve slower or partial adaptation.

- For complex, ambiguous future states (e.g., prolonged uncertainty, long-term caregiving), forecasting remains difficult and more error-prone.

Timeline: Major Life Events & Milestones

| Year | Milestone / Event |

| 1957 | Born on November 5 in Ithaca, NY. |

| Early–1980s | Undergraduate studies: BA in Psychology (University of Colorado Denver). |

| 1985 | PhD in Social Psychology (Princeton University). |

| 1985–1996 | Faculty at the University of Texas at Austin conducted early research on judgment and social cognition. |

| 1996 | Joins Harvard University as Edgar Pierce Professor. |

| 2003–2005 | Seminal papers on affective forecasting and related constructs have been published. |

| 2006 | Publishes Stumbling on Happiness. |

| 2007 | Book awarded Royal Society Prize for Science Books. |

| 2010s–2020s | Ongoing research, teaching, public engagement, lectures, and publications; continued influence in psychology and behavioral science. |

Pros & Cons

Pros

- Conceptual clarity: Emotive augur provides a unify structure for many everyday mistakes.

- Empirical support: Numerous experiments copy core effects (impact bias, focalism, immune neglect).

- Cross-disciplinary reach: Findings inform mentality, behavioral economics, healthcare, and public policy.

- Public communication: Stumbling on Happiness and public talks make science accessible.

Cons

- Possible overgeneralization: Not all scenarios or populations fit the patterns equally.

- Measurement concerns: Forecast vs. experience comparisons require careful operationalization.

- Simplification for popular audiences: Nuances may be glossed over in general-audience summaries.

FAQs

Answer: Daniel Todd Gilbert is an American social clinician, professor at Harvard University. He investigation how people predict (or mispredict) their future emotions, called affective prophesy and wrote the book Stumbling on Happiness.

Answer: Affective forecasting is when we try to predict how we’ll feel about future events. We often make mistakes: we tend to appreciate how strong our feelings will be, how long they will last, and underrate how quickly we adapt. Gilbert’s work shows these errors are regular and foreseeable.

Answer: Stumbling on Happiness (2006) explains Gilbert’s research in simple stories and investigations. It talks about why people misread happiness, how memory and curiosity play a part, and what people can do differently. Yes, it is very relevant today, since decision-making, well-being, and the mindset of happiness remain important in our private and public lives.

Answer: It helps you avoid obstructive expectations (for example,anticipate extreme happiness from one big event).

It teaches you to think about adaptation: how your feelings will settle.

It shows the importance of realistic forecasting (asking “how will I feel really months later?” not just “right after”).

Helps with coping when things go wrong: knowing you may adapt faster than you believe.

Answer: Critics argue that lab settings and question wording might inflate errors.

Some say individual and cultural differences need more study.

Others point out that for serious negative events, adaptation may be slower or incomplete.

Also that some simplification in popular writing may hide nuance.

Conclusion

Daniel (Dan) Gilbert’s scholarship develops how we think about happiness, conjecture, and conversion. By chronicling predictable ways people err when predicting their emotional futures, Gilbert provided tools to improve decision-making, recalibrate assumptions, and design policies that better account for human psychology. His Legacy blends rigorous trial with public transmission, a model for translating intellectual science into practical guidance.